Slots, Whales & Corvus

Jim DeFrance

September 11–October 30, 2021

STARS is pleased to present its first solo exhibition by Los Angeles artist Jim DeFrance (1940–2014). These nine pieces represent three distinct bodies of work from the beginning, middle and end of the artist’s more than half-century career as an abstract painter. Respectively, this consists of three “Slot” paintings from the mid-1960s, made just after DeFrance completed his MFA at UCLA with classmates Allan McCollum and Vija Celmins; three “Whale” paintings from 1990, made as commercial interest in his work began to wane amidst the art market crash and changing trends of the 1990s; and three “Corvus” paintings on birch wood made in 2012 and 2013, which were the final years of his life following more than a decade of serious health problems and alienation from the rapidly expanding art world.

A small posthumous retrospective curated by Tom Dowling and Trevor Norris in 2018 at the Frank M. Doyle Arts Pavilion at Orange Coast College in Costa Mesa reintroduced the breadth of DeFrance’s work to regional audiences and included a monograph collecting old and new writing about his practice for posterity. Nevertheless, DeFrance remains an obscure and seldom-discussed figure today, which is surprising considering his consistently excellent output that began in the twilight of Abstract Expressionism and extends all the way to the golden days of Instagram.

The selection of works presented here comprises an abbreviated survey illustrating DeFrance’s life story and artistic practice in three acts, as well as three notable moments in California art history that took place in parallel.

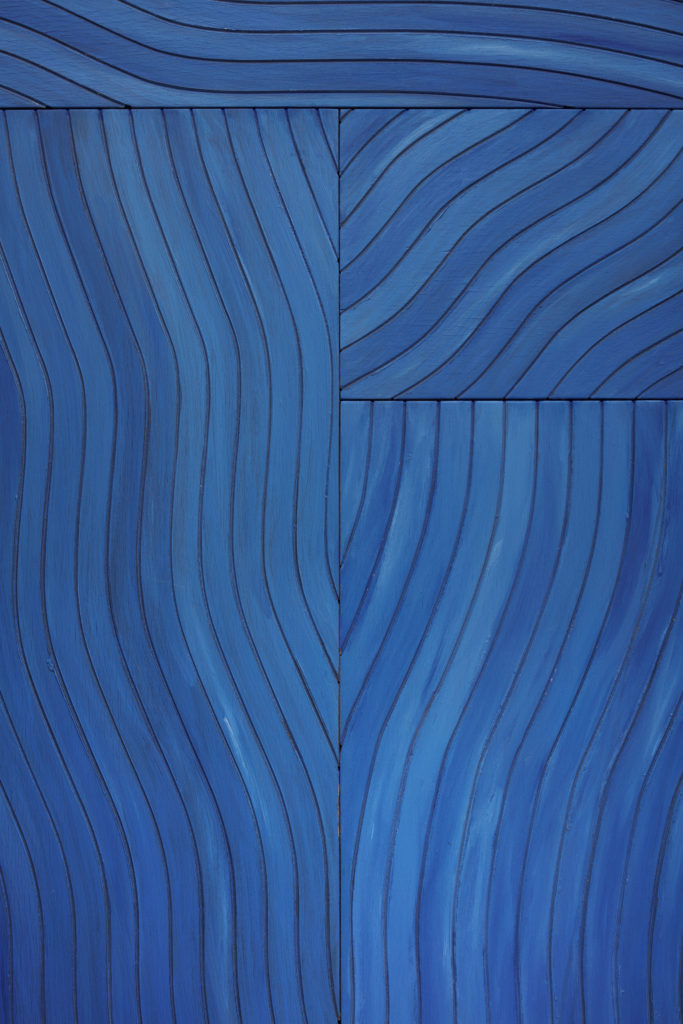

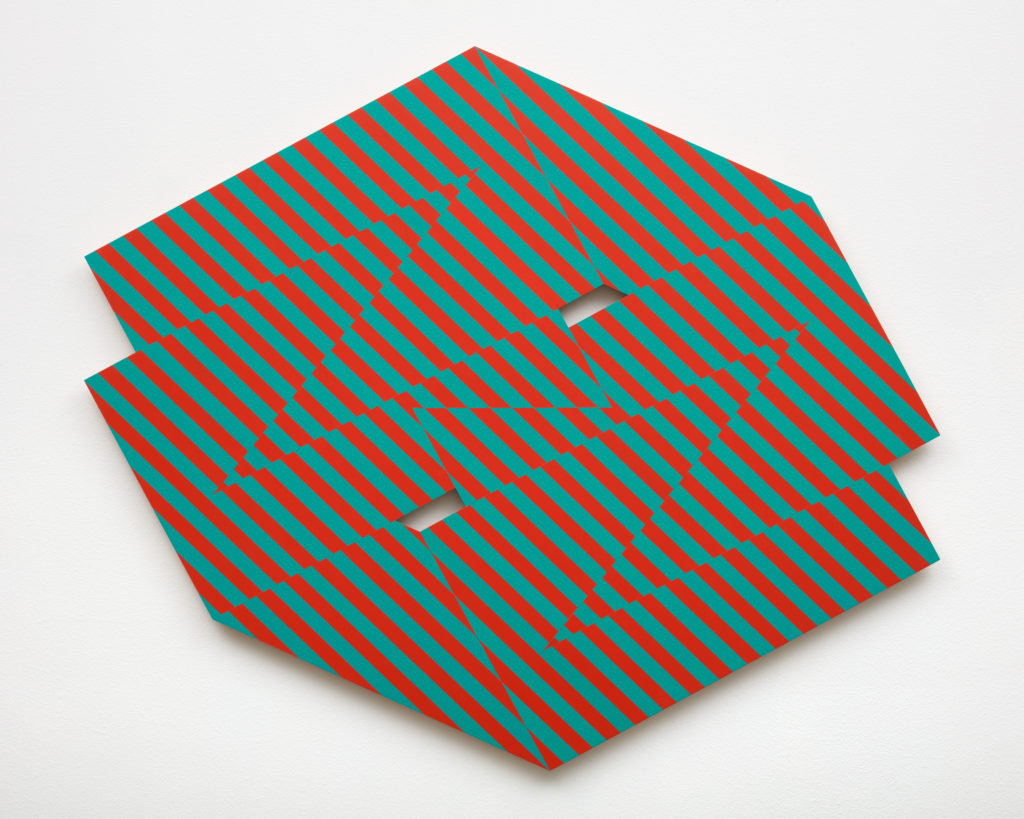

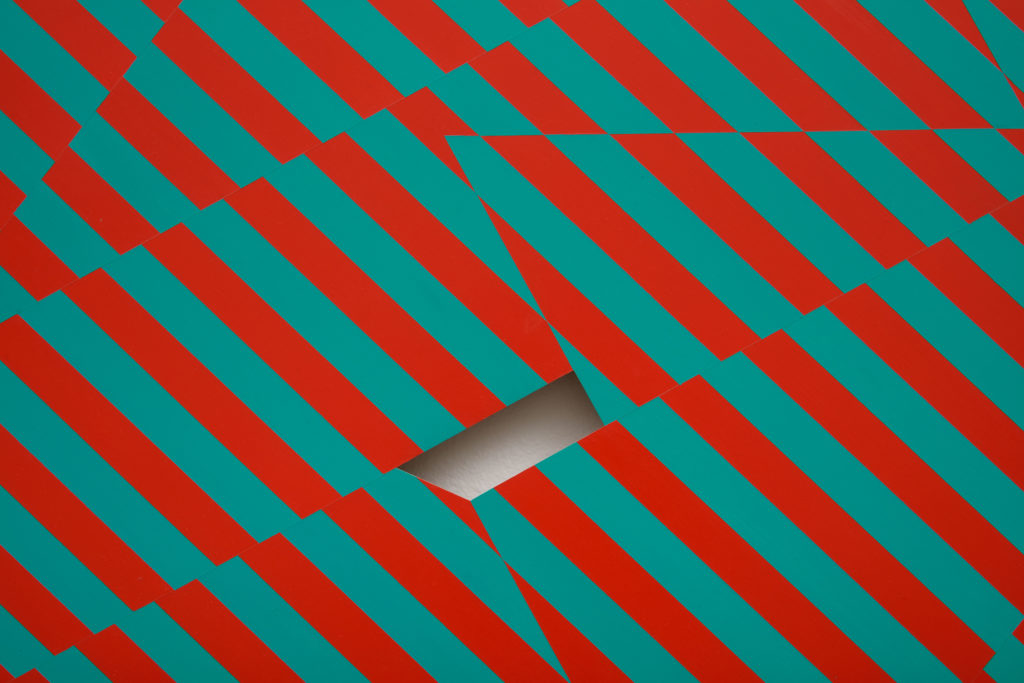

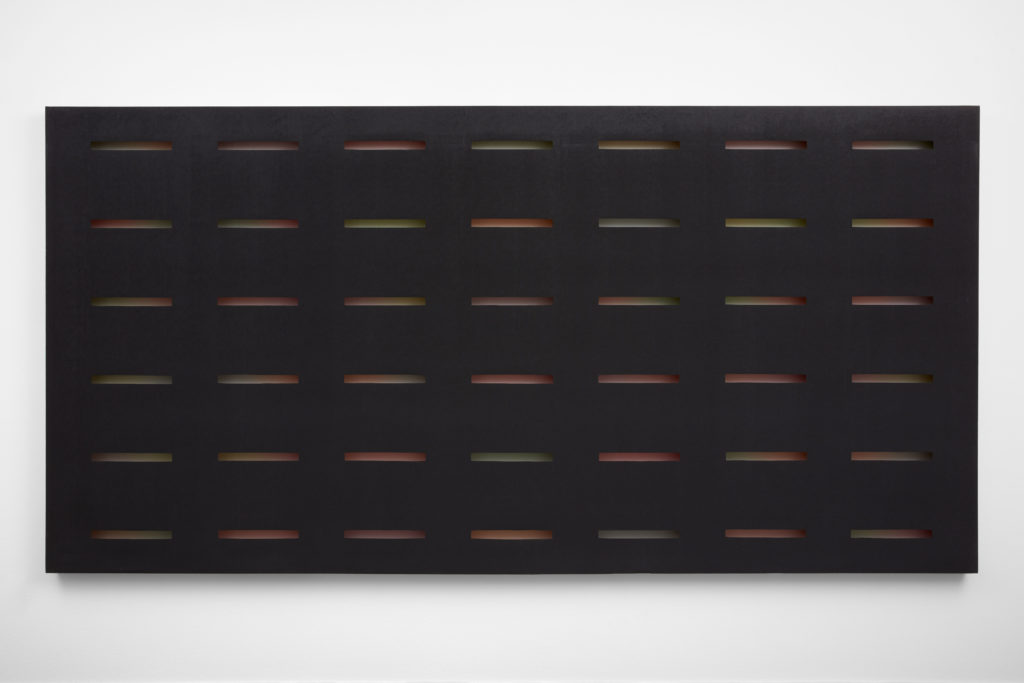

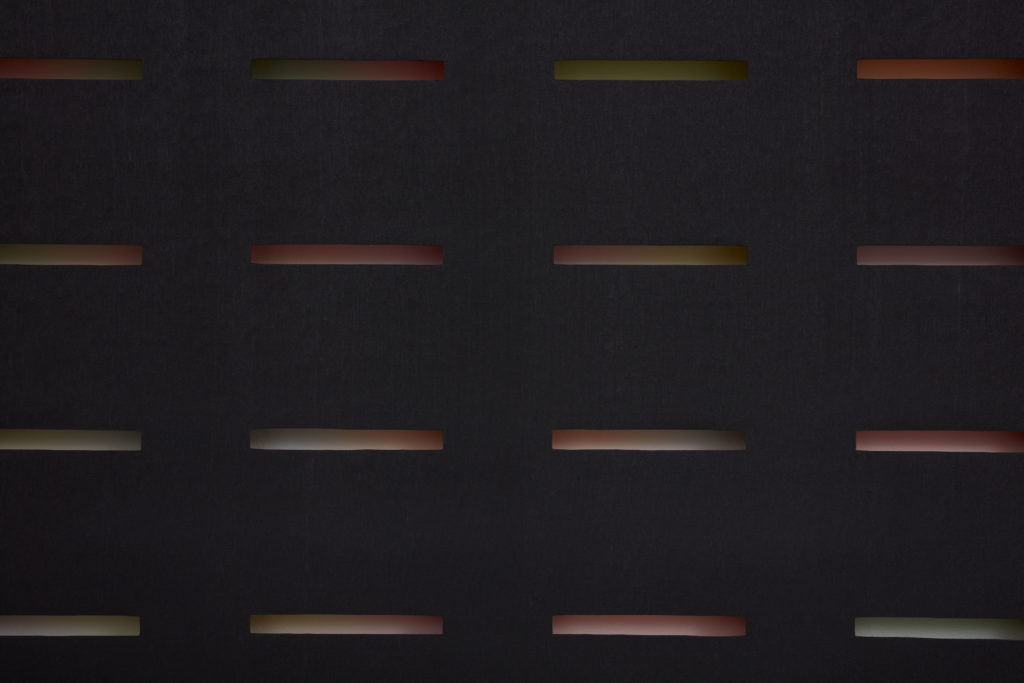

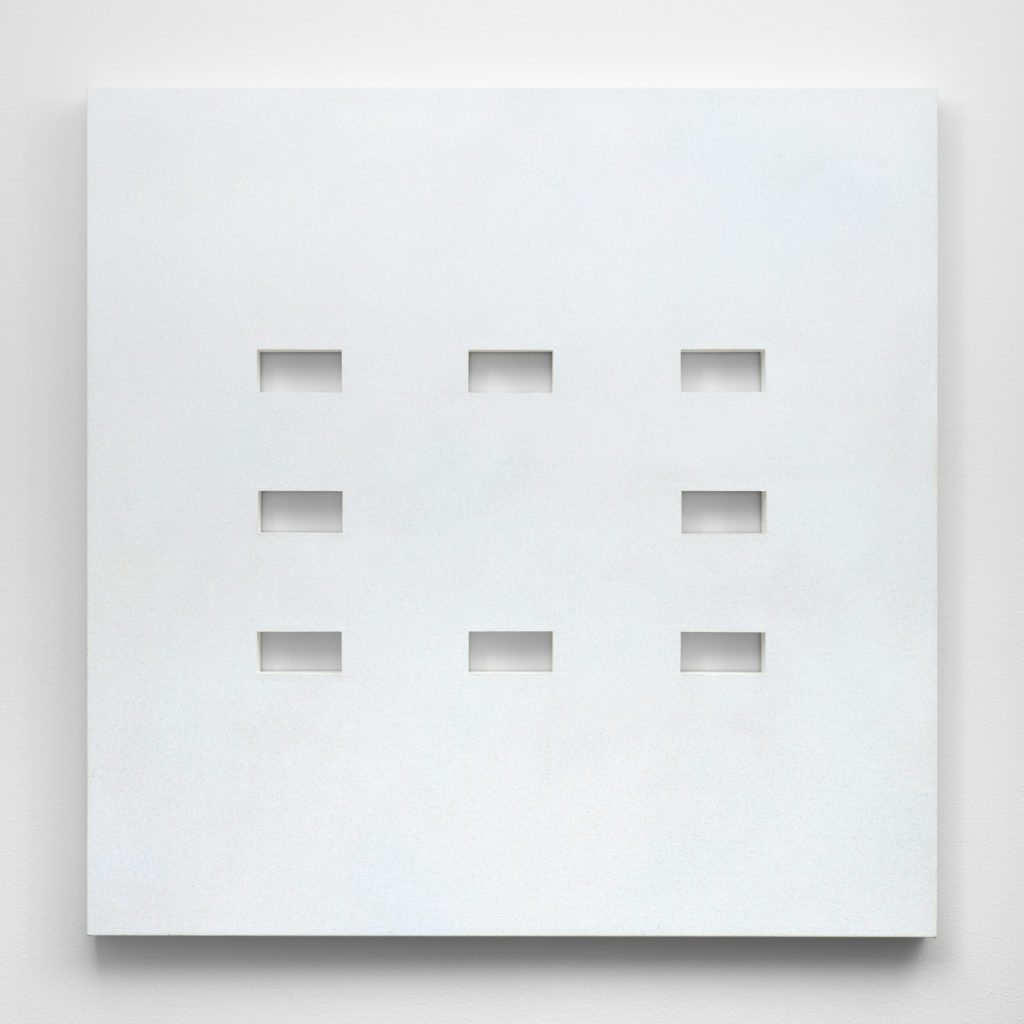

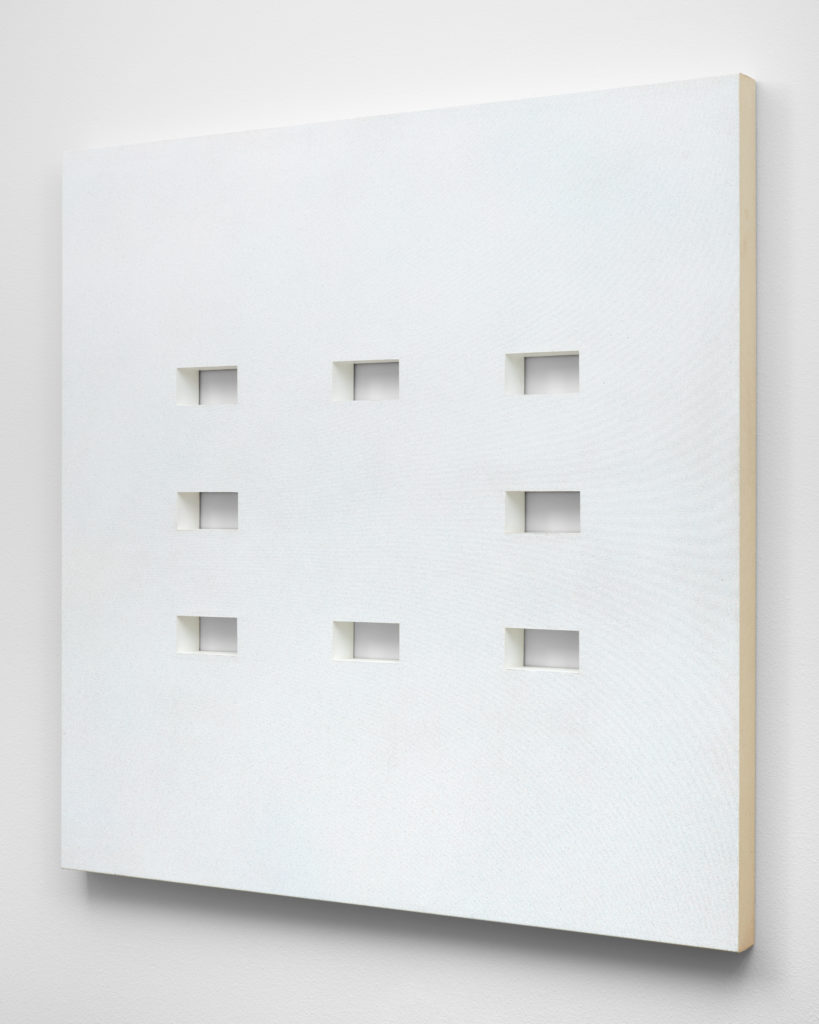

The Light and Space movement and the “Finish Fetish” style, a.k.a. the “L.A. Look,” of the 1960s are useful descriptive frames for Dazzler, 1965, a jagged assembly of optically reverberating turquoise and red acrylic lines painted on veneer. Like DeFrance’s two minimal works made the following year, Gray #3 and White #3, geometric shapes are cut out of Dazzler, highlighting the presence of such paintings as dimensional objects.

An admiringly ambivalent Artforum review by Joseph Mashek of DeFrance’s 1970 Sonnabend Gallery exhibition begins with, “what James de France has on view are “canvases,” but not exactly paintings.” The writer connects the work to crass words like “optics,” “popular science,” “decorator,” “taste,” and “gimmick”—not to dismiss DeFrance as superficial, but rather to hint at his complexity as not-not superficial, e.g, “It is easy enough to demonstrate that it is not only a gimmick… <but> it is still a gimmick too.” The critic makes tongue-in-cheek suggestions that these works would look better in a nice, modern house with good light—which stands true for most things, art or otherwise.

While DeFrance did not enjoy wealth during his lifetime, acquired from his painting career or by any other means, he is remembered by his milieu as someone who lived and worked in spaces he made strikingly beautiful. As his popularity as a frequent exhibitor on both coasts and beyond was peaking, a 1985 Los Angeles Times article by Meredith Preston profiled DeFrance’s loft in Downtown Los Angeles, with a headline that sounds as if it could have been Tweeted by a lifestyle outlet in 2021: “The Play of Light: Artist Jim DeFrance Transforms a Downtown Warehouse Into an Airy Studio-Home.”

It was shortly thereafter, in the wake of the 1987 Whittier earthquake, that he and his wife, artist Nancy Goss-DeFrance, decamped their gritty bohemian community downtown for a bucolic rental in the family neighborhood of Van Nuys in the San Fernando Valley. This coincided with seismic international changes in culture and the economy, as the rise of social libertarianism ushered in an explosion of mediums in 1990s contemporary art. In Los Angeles, installation artists like Mike Kelly and Paul McCarthy, photographers like Catherine Opie, and conceptualists like Barbara Kruger dominated discursive and market trends once led by painters. This time was a regional renaissance, however not one whose fashions fueled by subculture and identity included DeFrance’s personal brand of finely hewn formalism.

The three massive works on view from 1990, Baleen (gray whale), Mask 3 (blue whale), and Rainbow each feature rounded puzzle pieces of canvas assembled in cetacean formations. From the eponymous monochromes of the first two, to the prismatic color sequence of the latter, the surface of each is broken into undulating, concentric stripes that continue the legacy of his work from the 1960s and of obvious forbears like Frank Stella, who by this time traded flatness for a maximalist, almost sculptural approach to abstracting the canvas. As Christopher Knight wrote in a 2018 review of the Costa Mesa retrospective, as other artists were tinkering with the dematerialization of the art object, “DeFrance refused to let painting go.”

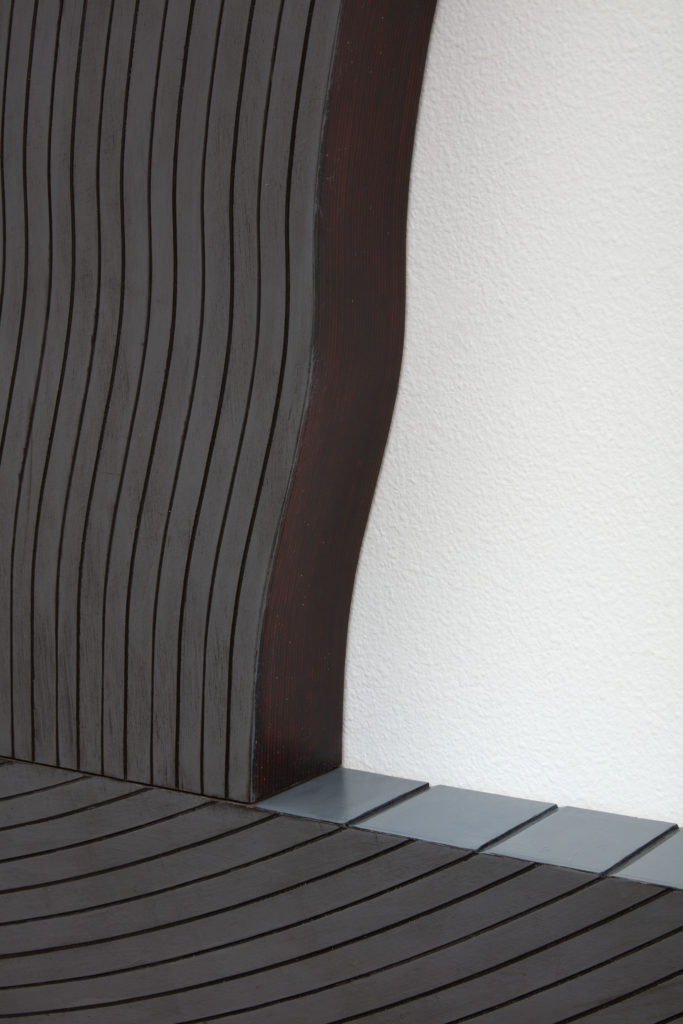

The same review began, “Oddly, if one juxtaposed an early painting with one of his last, it might initially look like two different artists had made them. The abstract motifs vary widely, but the survey also reveals a through-line of impeccable craftsmanship.” Three of these last works are included here, Corvus .03 and Toucano from 2012, and Corvus .05 from 2013,which showcase DeFrance’s skill as a woodworker. Gone is the canvas, instead the artist paints on hand-fabricated wooden shapes whose silhouettes hover between geometric and organic, whose flatness is supremely smooth, yet ample enough to cast a shadow on the wall on which they hang. Each is a surface that animates the corporeal nature of an object. The compositions are part black and midnight blue, with lavish emerald green sections that reveal the underlying birch grain.

Perhaps in 2021, not enough time has passed to synthesize the L.A. artist landscape of the mid-2010s with the same clarity as previous eras. However one can certainly point to these later Obama years as a time when Los Angeles’s identity as a commercial art hub expanded with fanfare and exuberance, just as art fairs, biennials and private museums proliferated internationally at an unsustainable pace. Growing popular interest in visual culture as a source of sensorial experiences that could be commodified and documented via social media led new audiences to contemporary art as content. As this trajectory has continued, once intractable distinctions between art, design and decor have weakened their hold over systems of value. (“Taste” is no longer the dirty word it was in 1985). Today these last works by DeFrance, in all their electric ambiguity, resonate as a compelling alternate ending to a well-known story about painting that began some fifty years ago.

– Kevin McGarry, 2021