Anarchist’s Vacation

Danny Bredar

November 12–January 21, 2023

This past June, Danny Bredar appeared in Italy. Masaccio and Piero della Francesca had always emitted a distant light for the artist, but he’d hardly conceived of what it might be like to see their work up close, to see his vision reflected back at him. Now he was there—Florence, Monterchi, Arezzo, the cradle of Western painting culture. What quest or grail could be found within the classical overload? Inevitably, he’d depart the glinting frescos without answers, eat some spaghetti alle vongole, and keep driving.

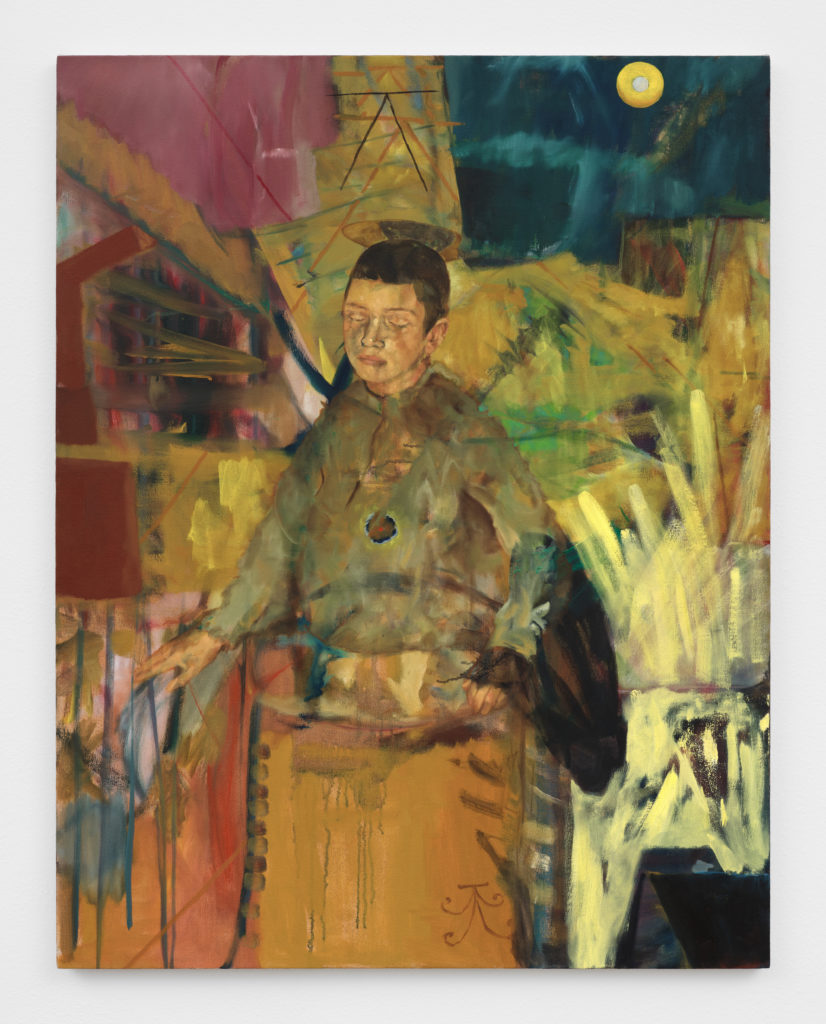

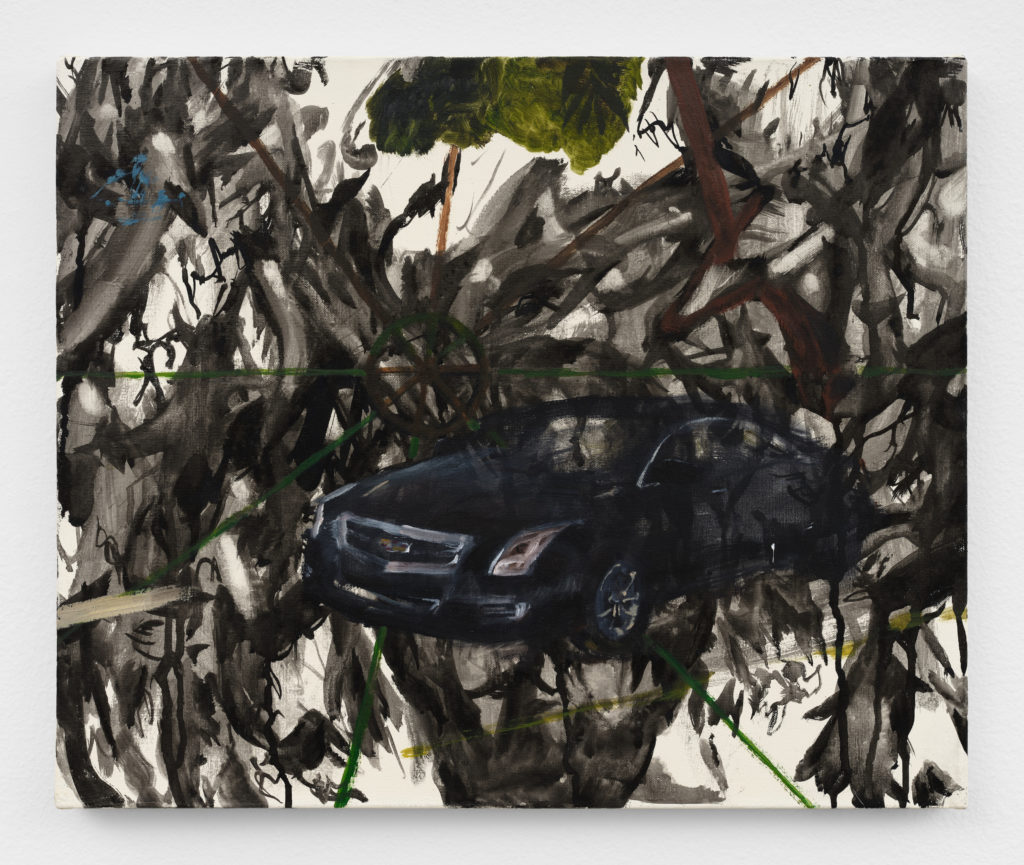

Taking it easy but having some serious business to attend to: this is Bredar’s notion of the Anarchist’s Vacation, in which the artist/hero/clown hovers above his own consciousness in a mixture of detachment and self-critical imagination. Channeling the omniscient third-person perspective of video games or novels, he projects his perception beyond his present-tense bodily experience—he’s right here and over there, inside and outside, stationary and on the move. These maneuvers are orchestrated as though from the cockpit of a rented Cadillac, engulfed by or emerging from a thicket of Sumi ink, its front left tire re-presented as a wheelwright’s wheel. Within this painting and across the exhibition, in a series of feints and parries, Bredar spins the wheel of difference: green and brown, up and down, leaf and branch, field and form, text and paratext, asking what is retained and what is effaced by the high-beam light of doubt.

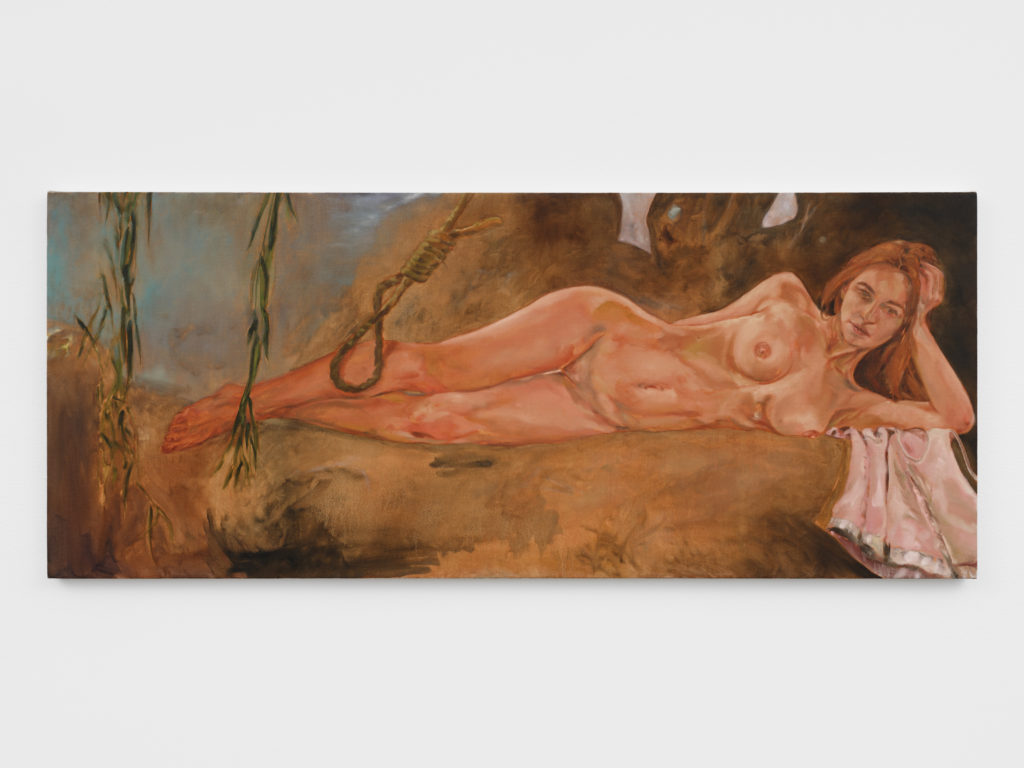

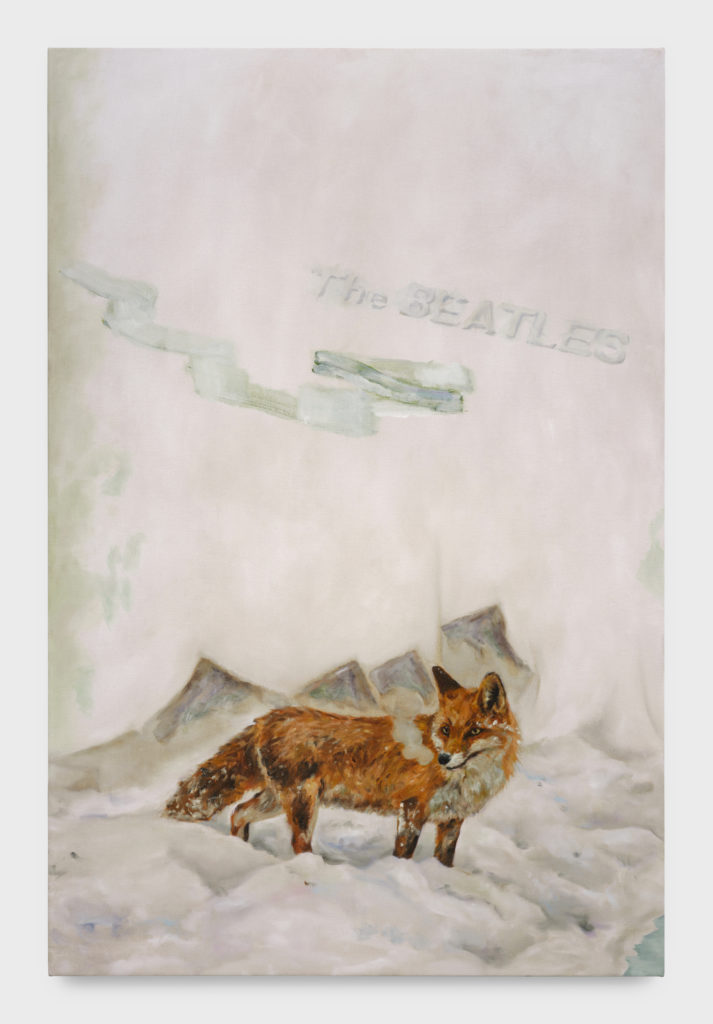

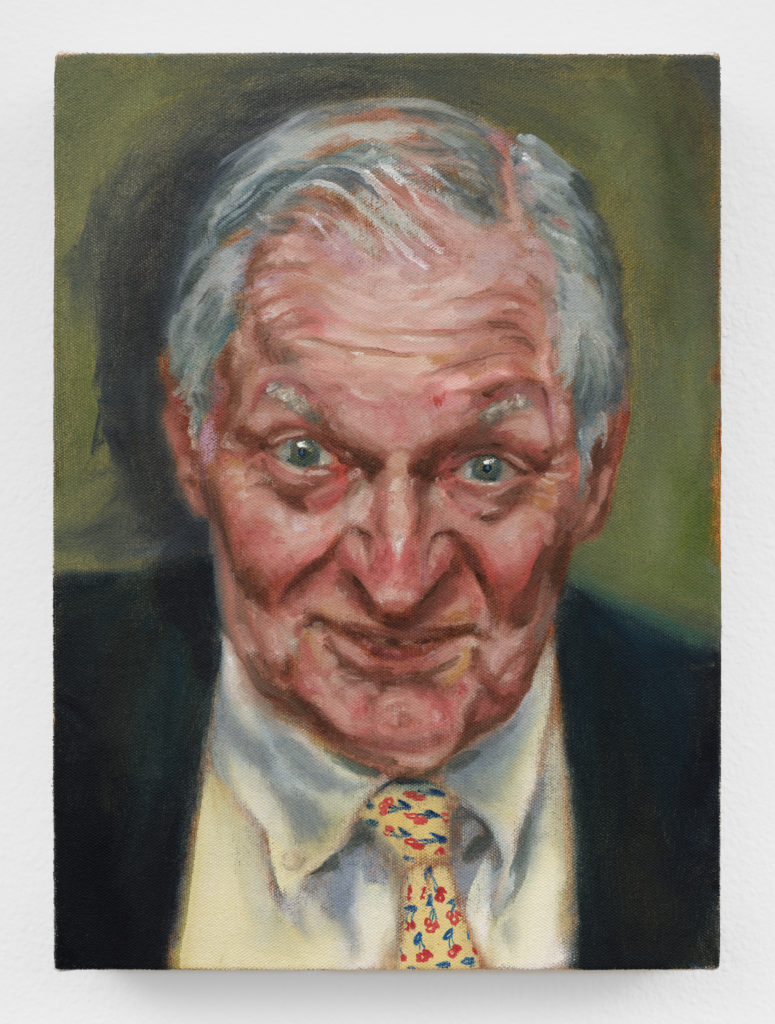

Each element in Bredar’s exhibition contributes to the Italian allegory while casting the viewer dangerously off-track. Wine turns back to water in Brukhal, which depicts the grieving relatives of an electrician turned fallen soldier in the Ukrainian resistance. A Sienese-ish snowscape, stalked by a red fox, rises from the blank ground of the Beatles’s “postmodern” White Album. Monterchi, a key stop on the so-called Piero Trail, congeals without apology into a turkey. In a flagellation scene, one crash-test dummy strikes another with STARS’s pink curtain—next to which the painting hangs in real space. Meanwhile, in each of the gallery’s two rooms, the artist has placed a tabletop flush to the floor and set a folding chair atop it. These works, titled People Materials Environment, remind us that there is nowhere to sit still; they suggest that the gallery is flooded, that the paintings function not only within their networks of internal and interconnected signification, but also within the ambit of industrial emotion and the historical readymade, the spheres of value production in which the artist seeks to make his mark, or to grasp what his marks add up to.

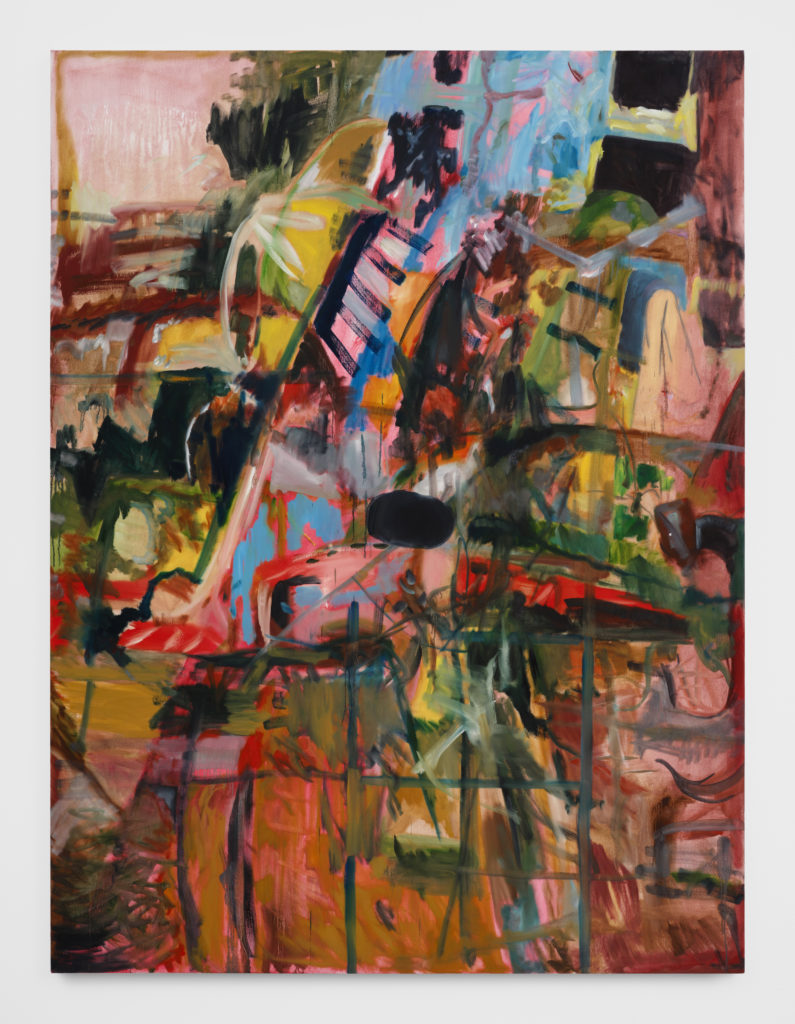

Twenty-four years ago, when Bredar was a child, his mother died in a car accident that he and his older brother survived. As an origin story, the tale is as ambiguous as it is harrowing: How to respond to the total collapse of meaning? Bredar, with his catholicity of style and subject and affect, might be seen as proposing an anti-painting response, a strategy of refusal. Instead he implies that there is real knowledge gained in resisting the monopolization of artistic behavior and the general pressure of self-conformity. His work, with its ethic of arcane connectedness, of constructed disarticulation, traces a path beyond dumbing things down or throwing up one’s hands—a third path of moving adjacently, of slipping through the cracks in resolution, of following the friction where one’s alienation from one’s own body brings about the chance of inhuman comprehension. Yes, it’s true: there is a black hole at the center of our endeavors, as Bredar demonstrates in Awareness of Annihilation, 1580-2036, which he painted lusciously in one session for the express purpose of furnishing the exhibition with a large abstract. This absence might represent annihilation, or it might indicate an arrival at the true blank meaning of something. We ricochet against aporia and end up back in the diversified field of all of our experiences, sensations, and encounters. As Bredar puts it, “I can’t be too cynical or obliterated, because for me there are genuine stakes in producing some kind of understanding or record, even if it can’t be easily said.”

–Daniel Wenger, 2022

Danny Bredar (b. 1992, Denver, CO) lives and works in Chicago, IL. He received his MFA from SAIC in 2019 and his BA from Harvard University in 2014. Recent solo and group exhibitions include Rhona Hoffman Gallery, David Lewis Gallery, Caffé Centrale (Monte Castello di Vibio, Umbria), and The Arts Club of Chicago. Bredar’s work has been exhibited at Soccer Club Club, Taqueria Los Alamos, the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts at Harvard University, the Armory Show 2020, the Elmhurst Art Museum, Taos Center for the Visual Arts, Sullivan Galleries, Sandbox Industries, Extase, and with the fictional gallery Currency in Münster and Zurich. Bredar also collaborates with Leah Ke Yi Zheng, with whom he received a 2019-22 Fellowship at The Arts Club of Chicago.