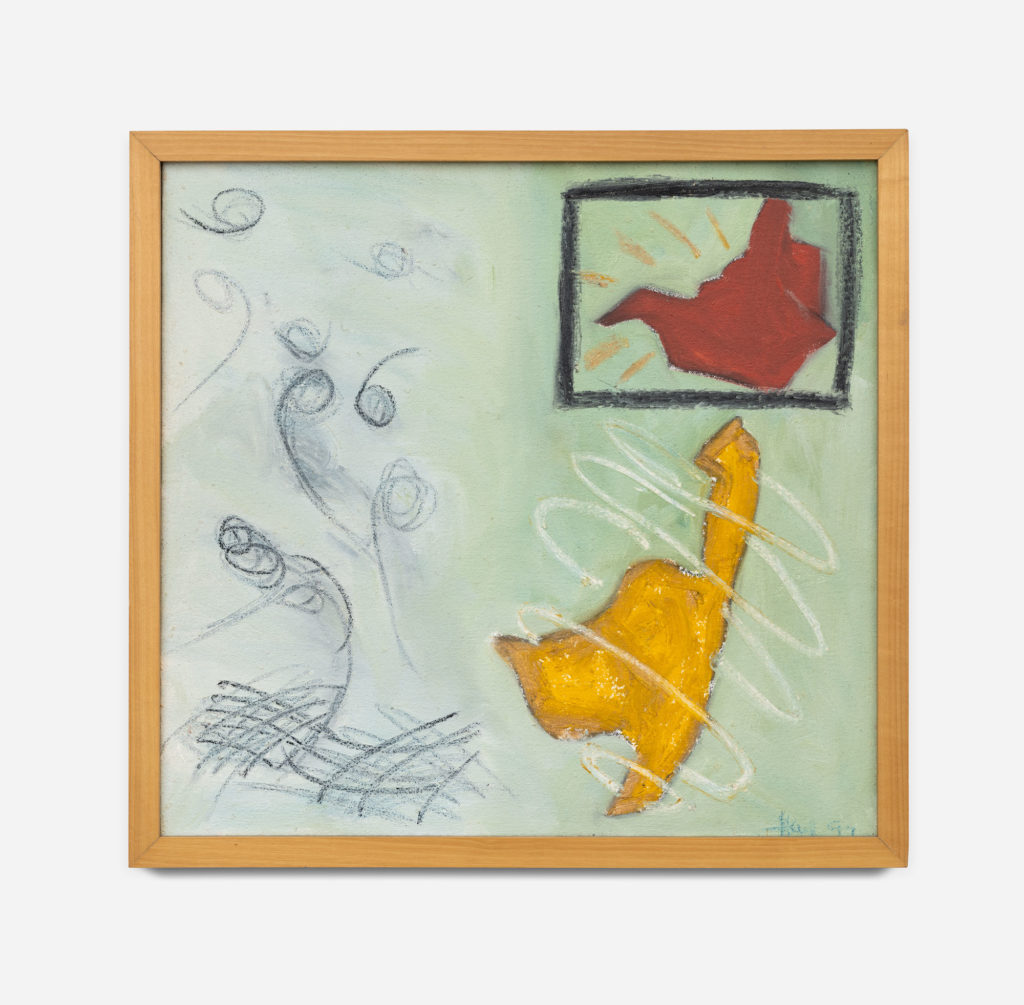

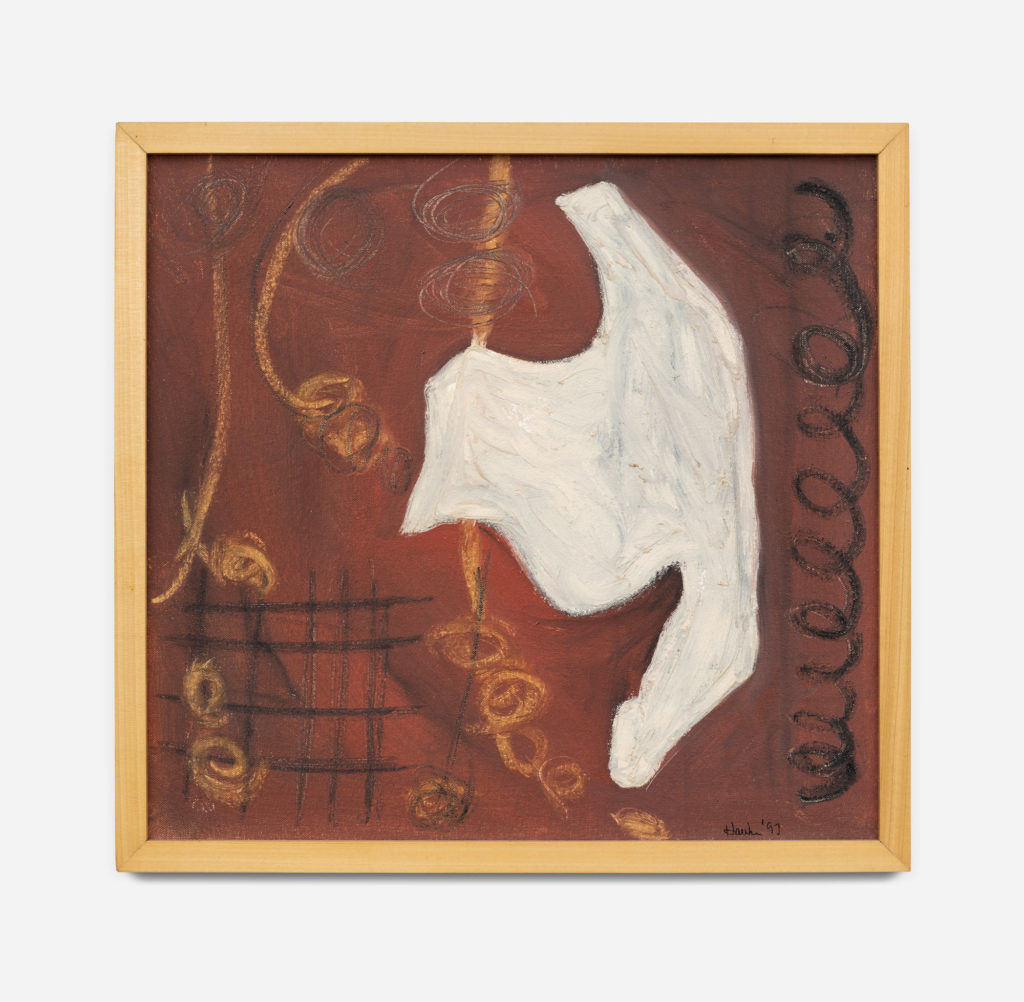

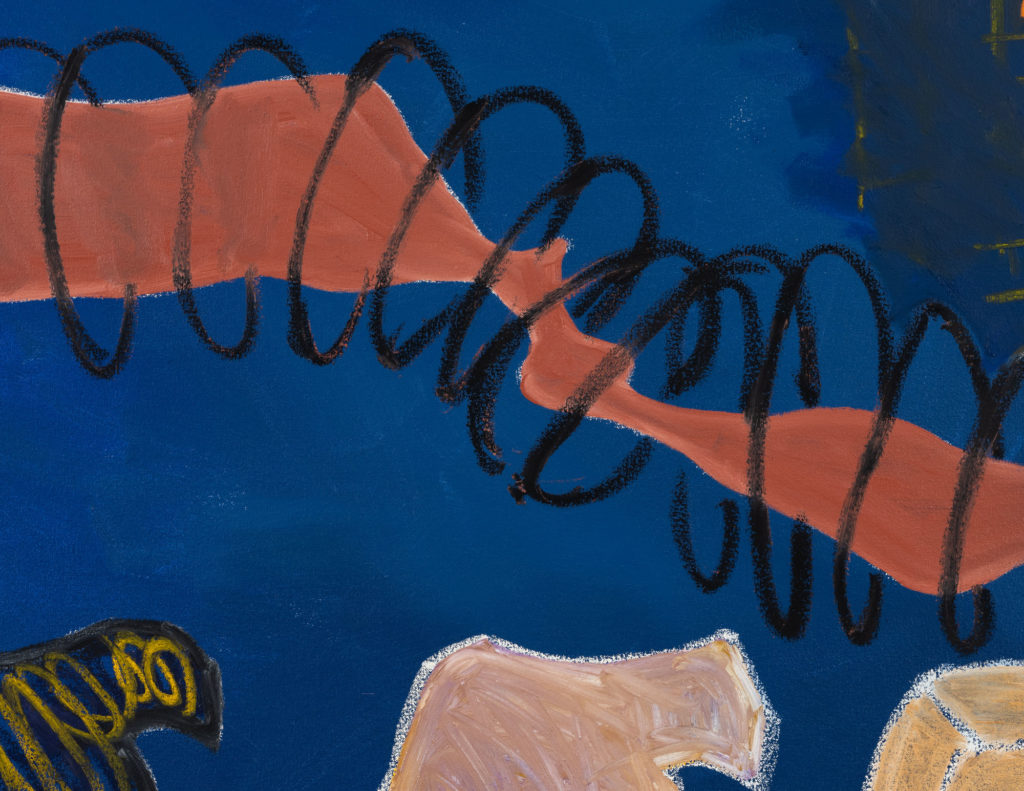

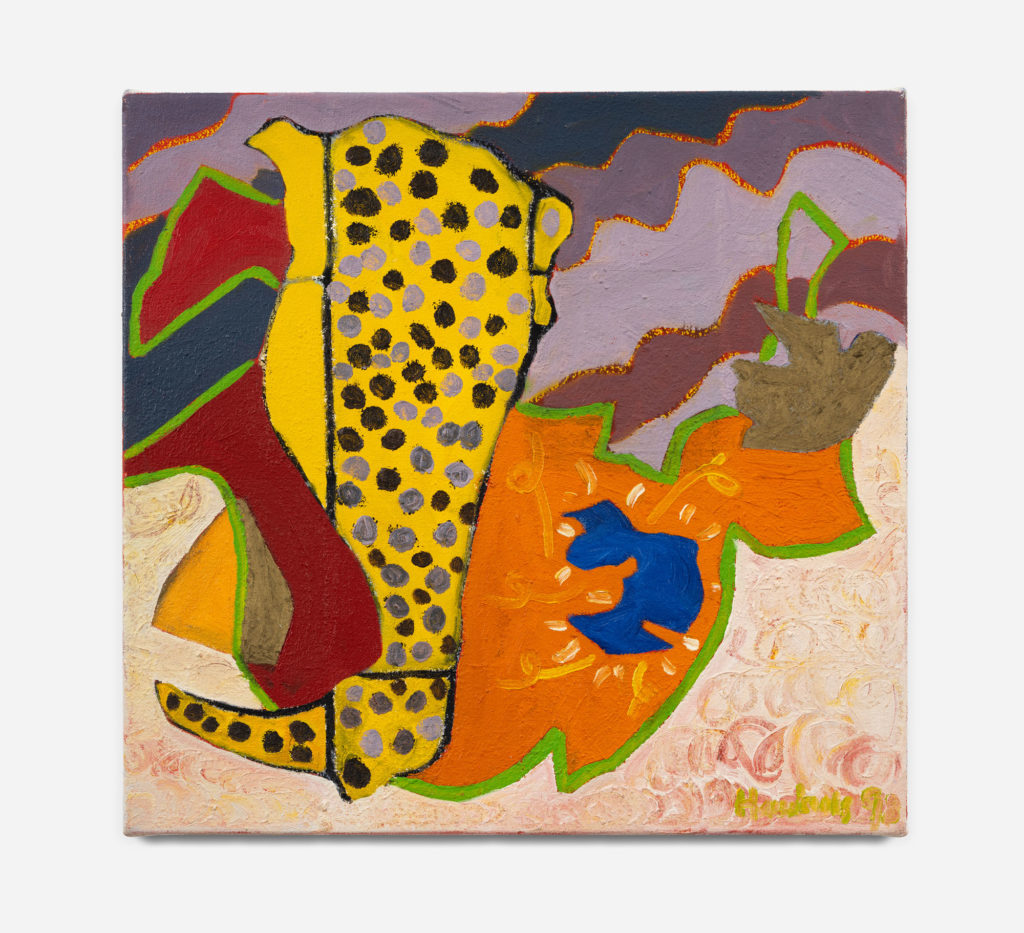

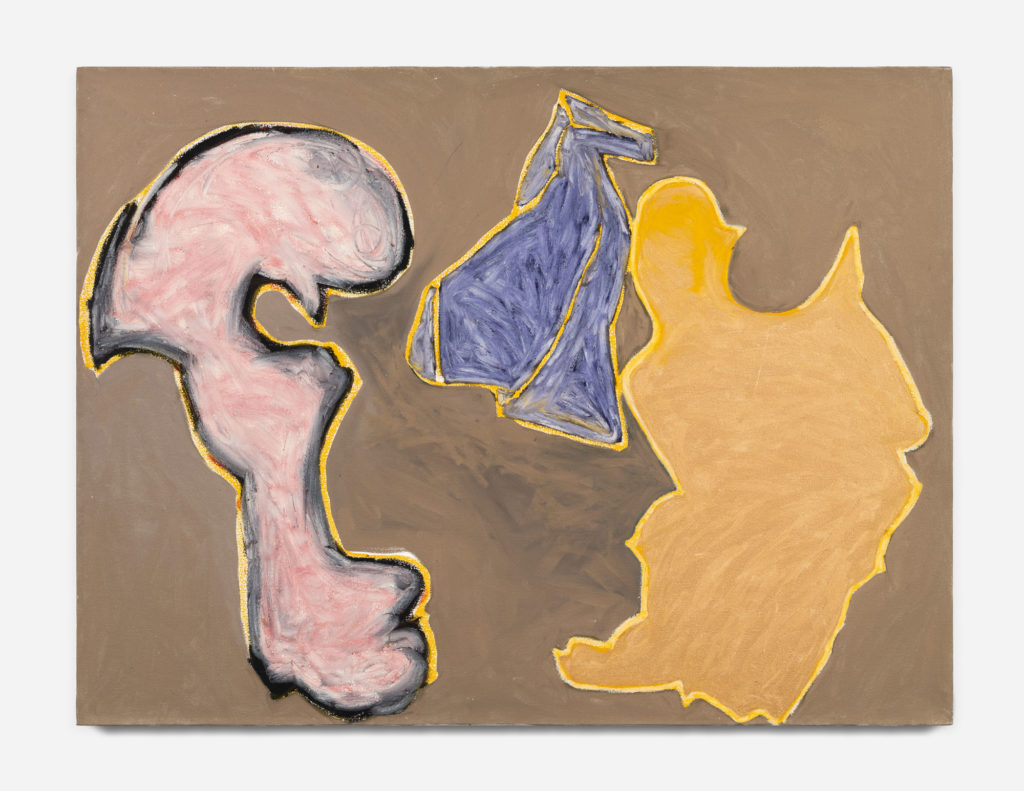

Natural Things, 1996–99

Cynthia Hawkins

February 5–March 26, 2022

Please email us for a recording of the conversation between Cynthia Hawkins and curator and writer Lauren Mackler that took place on Sunday, March 20 on the occasion of Hawkins’s current exhibition.

STARS is pleased to present Natural Things, 1996–99, the first exhibition in Los Angeles of work by the Rochester-based artist Cynthia Hawkins. In the late 70s and 80s, as a young artist in New York City, Hawkins exhibited in influential venues including Just Above Midtown, Clocktower, Artists Space, Kenkeleba Gallery, Cinque Gallery, and the Studio Museum in Harlem, where she was an Artist-in-Residence in 1987–88. Since then she has worked as a painter, curator, and academic, having received a doctorate degree in American Studies from the University of Buffalo, SUNY with a dissertation titled, “African American Agency and the Art Object, 1868-1917.”

As a painter, Hawkins has spent nearly five decades building a visual vocabulary of abstract forms derived from investigations into scientific, celestial and natural phenomena. Working in loose series, Hawkins is constantly repeating, evolving and adding to her own index of forms, allowing shapes to perform differently each time they are used. In her lyrical compositions, gravitational forces are illustrated through lines, grids, arrows, masses in orbit, and patches of color, with a palette that is both sophisticated and unpredictable, aside from a single series made in the 80s focused on the color green.

Natural Things, as the title implies, uses imagery from the natural world such as rock formations and patterns of sunlight through the trees as source material. Far from faithful reproductions, Hawkins intuitively distorts her subjects with energetic layers of color and pattern. As is emblematic of her practice, Natural Things proposes an alternative way of seeing the world around us.

Cynthia Hawkins received a BA in Art from CUNY, Queens College, an MFA from Maryland Institute, College of Art, an MA in Museum Studies from Seton Hall University, and earned a Ph.D. in American Studies from the University of Buffalo, SUNY. Until recently she was gallery director and curator at the Bertha V.B. Lederer Gallery at SUNY Geneseo.

Below is a short interview from December 2021 between the artist and Julia Trotta, who organized the exhibition at STARS.

JT: Where are you from?

CH: I’m originally from Flushing, Queens, New York. I grew up across the street from Queens College where I ended up getting my BA in Art, which was sort of unexpected because I thought I was going to be a History major. I walked through the Art Department late one night with some friends and saw the ceramics studio and thought, “Oh, I think I want to do that.” I never did any ceramics, but it was just the idea. Back then if you were going to be in the Art Department you had to take a year of courses first and then had to be approved to be a major. I did a lot of work and they said to me, “What are you going to do if we don’t let you in the department?,” and I said, “I’m going to make art anyway.” So they let me in. I don’t recall any other art majors of color when I attended Queens College. I don’t think it bothered me. I grew up across the street from the college in a city housing development, and it was middle class and mostly white. So I grew up in a mixed race environment.

JT: Once you were an art major did you have to choose a discipline? Did you study painting?

CH: I studied painting. I never tried ceramics, I only made tools when I needed something. I was a painter. Absolutely. When I was very very young I used to look at Gardener’s History of Art. I periodically borrowed it from the library and tried to read it. I was like, 11. I never got beyond prehistoric art. Because I read that chapter so many times it really stayed with me, especially the Cycladic figures. Actually the best art history paper I wrote in college was on the Cycladic figurines, so it was part of my foundation, those ancient shapes and forms.

JT: How did you start showing your work?

CH: That is really elusive. Some of the early shows I was in were around “artists of color” or “women.” I had a show at Just Above Midtown when I was 28. Linda Bryant would tell us to submit our work, or someone she/we knew curated an exhibit. I went to Just Above Midtown often. I visited Cinque Gallery often, too. Even before I had a show at Cinque, I’d always stop in there and talk to Ruth Jett, who was the director. I had a residency at the Studio Museum, but I just knew other artists and other women artists. There was a time when I was a part of a group of around ten women artists, and we used to meet once or twice a month at each other’s places. We discussed our current work, members would hear about exhibition opportunities and we’d tell each other. New York then was in some ways a challenge. It depended on your relationships. I went to galleries or sent them my slides or went to speak with them in person. Some gallerists even came to my studio on 83rd street. They would tell me my work was great, but they couldn’t give me a show. The other opportunities were all basically with nonprofits, or shows that let audiences know they were working on diversity. But very few of us exhibited in galleries.

JT: And so when people would come to your studio and say they liked your work but couldn’t show it, was the reason implied?

CH: The implication was they couldn’t show a Black artist. And I knew people who were part of galleries downtown, and they’d tell me that I couldn’t get a show or be in a group exhibit downtown because it was totally closed to us. And it was. And that’s why Cinque was started. That’s why Just Above Midtown started. We just sort of lived with that stuff, but fortunately there were alternatives.

JT: Are there people that come to mind who were particularly influential to you during that period?

CH: I had a very good friend, Irene Wheeler, who was a ceramicist, a ceramic sculptor. I met her at Queens College, she was quite a bit older than me. I was in my 20s, and she was in her 50s. Charming, lovely, generous person. It was through her that I met Norman Lewis, Romare Bearden, and Ernie Crichlow. At Kenkeleba House on 2nd Street, I met Corrine Jennings and Joe Overstreet. I’m still very involved with Kenkeleba. In the same period I met Camille Billops, who was an impressive woman. It was because I forged a relationship with Camille that I was interviewed for Hatch-Billops Magazine “Artists and Influence.” I met David Hammons on 57th Street at Just Above Midtown. I had a piece in their 1978 summer show “It’s a Crowd!” Other artists that come to mind are Vivian Brown and Emma Amos. It’s surprising how one forgets the important moments, important connections. I used to call Emma every now and then, and she would always say, “I’m working, what is it?” When you grow up in Queens, you’re outside of the loop really. One of the biggest misgivings I have is that many African American artists who were working lived in Harlem or other parts of Manhattan. Palmer Hayden was still alive when I was in college. I knew nothing about any of them.

JT: Because Queens wasn’t the hub of the avant-garde in New York?

CH: Yes, but also how would I know? I didn’t know anybody. They didn’t include Black artists in American art history, and that’s what propels my research. It’s about recovering all of these people who were left out of—never mind the cannon—but the general history of art in America.

JT: Were you aware of people like Romare Bearden and Norman Lewis prior to meeting them?

CH: No. Not before Irene told me about them. I didn’t know anything.

JT: So being in New York and meeting people was one kind of education, but you went on to get a MFA, an MA, and a PhD. What drove you from being a working artist in New York to then thinking about getting an MFA?

CH: The reason I wanted to get an MFA was that if I had to have a job, I wanted to teach art, that’s why I did it. I never expected it would be such a ridiculous challenge to get a teaching job. I had a few adjunct teaching jobs in New Jersey and Manhattan, then I finally got hired as an adjunct at Rockland Community College. While there I began curating exhibitions for the library.

JT: What drove you to do that?

CH: I wanted to expand my own experiences and support other artists. Later I worked at Ramapo College. I organized exhibitions there including a show of drawings by toddlers. It was terrific. They had a little opening and it was really sweet. I knew the woman who ran the childcare center and she had thousands of drawings by these little people.

JT: Then you went on to get an MA in Museum Studies so what was the angle with that? Did curating the exhibitions trigger an interest in the structural way that art is shared with the public?

CH: I’d like to say that, but I had gotten a job at Cedar Crest College as the gallery director. When I left there, I thought, how am I going to get another job as a gallery director? I also realized the field of arts administration was really beginning to develop. How was I going to compete with all of these people who are a lot younger than me? My experience at Cedar Crest made me realize there were things I didn’t know. I wanted to enhance my skill set, but it was also very practical. I’m not very good at mundane jobs–I could never be a waitress because I’m not that pleasant.

JT: What was your focus within Museum Studies?

CH: I was supposed to choose a field, but I didn’t, so they put me in Museum Management. Petra Chu was the head of the department at the time. She was extremely supportive of me. She interviewed me in 2005, and I mentioned a book I wanted to write about Black printmakers–she still asks me about it to this day. The museum professions program was wonderful. Three semesters in, I thought I’d get a little part-time position at some gallery or museum. I didn’t think I’d get an actual job but I ended up being hired as the gallery director at SUNY Geneseo.

JT: But then you got your PhD in American Studies, so what was that chapter?

CH: That chapter was really about me wanting to know why the United States is the way it is. Why the world is the way it is. And for me, it really comes full circle because of my interest in history; I had been interested in it since middle school. I wanted to combine art history with history and theory. I really wanted an interdisciplinary understanding of history and art.

JT: With your doctoral studies, what period was your focus?

CH: Late 19th to early 20th century, my dissertation covers 1868–1917 (“African American Agency and the Art Object 1868-1917”). I was looking at the rise of artists of color and the way that work was interpreted by the artists, by their community, and instilling another kind of agency in the Black community that worked toward equity. So it covers a few different eras to map out the shifts in the collecting of, the uses of, and performance of art for African Americans.

JT: That’s a pretty dense subject. So you were doing all this research and you also had your studio practice, a job, and you were raising children. How did you manage to do all that?

CH: I don’t know. In the 80s my daughter was in her playpen in my studio. I don’t know–I just did it. Until I got the job at Geneseo I always had part-time work. In 2006-07, my kids were in middle school and high school and that freed up my time. The MA program at Seton Hall was in the evening; I would drive an hour and a half each way. What was I thinking?

JT: Wow! I’m trying to calculate how you fit everything into the day. So from all of this research and writing that you were doing, is there a way you think it might have filtered into the paintings you were making?

CH: I totally compartmentalized. It was all separate. The writing was the hardest part. One of the reasons I went to get a PhD was so that I could write that printmaking book.

JT: So the subject of the book is African American printmaking?

CH: Yes, it’s big. It’s broad. Because there were printmakers all over the country, and they all had very different social experiences. In Tennessee, out west in California. And then I had to decide if they had to be full-time printmakers, or can they be painters and sculptors who do printmaking? Part of getting my PhD was to teach me how to write. And it has. But it’s also so different from painting. Painting…just feels like… painting is part of me. Even though it is still intellectual work.

JT: So you would go into your studio and not necessarily take on all the research and information you had absorbed?

CH: That kind of research, if I were going to bring it in, would change my practice.

JT: I’m not sure you look at it this way, but maybe it’s all your practice? Just different tentacles?

CH: Yes, it is all a part of what interests me; I also find it motivating.

JT: So let’s talk about your Natural Things series. It started in the 90s?

CH: I can say that Natural Things started in 1996. But that’s not true. There are five or six paintings called Natural Forms that came before Natural Things, and before those there was a series of graphite drawings that were also titled Natural Forms. Then Natural Forms became Natural Things, and then they became Natural Things Part II.

JT: So it’s more of an evolution of work. We’re taking a snapshot of one starting point and ending point, but it isn’t necessarily the beginning or the end.

CH: Right.

JT: How did this evolution come about? What were you exploring? Were you looking at the natural world? How did you create these forms?

CH: What I was looking at was the environment. The impressions in the soil, the shapes of rocks, pebbles, boulders, the way the light fell through the trees, and the way the sun, when it’s setting, shines yellow on the ground between the trees–all those shapes. Later it got extended and transformed into the Signs of Civilization series, which were naturally occurring forms at 30,000 feet: the shapes of the landscape, the way the land has been divided up. It was still very abstract. I was not interested in making landscapes or copying nature at all, but taking these shapes and forms to create something different, to make them behave differently.

JT: There are recurring shapes and figures. Sometimes they morph. Did you have a set of “characters” from photographs or memory?

CH: I would make sketches of shapes, and I sort of collected them. So for the Currency of Meaning series, there are arrows, circles and triangles, which became part of my vocabulary, my toolbox. Then these new forms were added, and for me they remain new. Every time I use them, they are used differently and function differently. They can be on the ground and weighted, or they can also be floating; they can react to gravity or not. They’re my vocabulary.

JT: How do you approach composition? There is a real ecosystem within each painting with its own push and pull and balance. Is that approach to creating balance part of your intention?

CH: Years ago I would do a lot of drawings before I made a painting. I just found a lot of drawings from the 70s, and I’m surprised because I don’t do that very much anymore. Now if I make a shape that I like, I leave it, but all over the rest of the surface of the painting, new things can happen. I just keep applying paint until it comes together. I often ask what it needs. The other day I said to myself, why are there so many details in an abstract painting that need to be dealt with? I’m almost done, but then I have these details to fix and finesse. Why does an abstract painting need detailing?

JT: You’ll have to ask the paintings that question. Are there themes that have been part of an ongoing investigation that unite all or most of your work?

CH: I’d say that even though I’ve been using natural forms for quite a long time, I still think it has a lot to do equally with science and space. I get space in my work through color relationships and positioning of forms. I allow natural forms to become something else. I actually insist on it. I appreciate their existence in the world as such, as they are, but my job is to reinvent them.

JT: What do you feel are the stakes or the potential of abstraction? Both generally and for yourself as an artist?

CH: I have never been tempted to not work abstractly. I do know that there has been reluctance on the part of many people to accept abstract work from a Black woman artist, although there have been quite a few. I feel, especially in the ferment of recent years, that my continuing commitment is an act of resistance. I stick to my own goals and my own methods, but there is more than one way to communicate with people. I’m certain that politics and one’s responses to social conditions are harder to read through abstraction, but I have no problem asking people to work a little harder. I would like people to walk by my paintings and feel joy. That would be nice.

JT: I read the talk that you gave recently that was specifically on the subject of abstraction and its political potential. In it you say that “abstract works of art offer the artist many different possibilities to reframe and discuss political and social issues extant at any moment in our evolving society.” So I was thinking about that statement as it applies to you. What are you thinking about in a political or social context that is getting filtered into the work you’re doing right now?

CH: I have completed one piece in the last two years called Oxygen that was made specifically thinking about George Floyd and other people who were choked to death. A lot of the work that was in the exhibition I was referring to in that talk were addressing social issues, and I could see, if one researches symbols in a work, that it’s meant to be read to be a certain way even if it’s abstract. I feel that what I do is my expression of freedom and resistance to those bodies that even still would like to presume one is not smart enough or intellectual enough or read enough to use these narratives to make work. This idea that Black artists have to be making figurative work, to talk about Black issues, social issues is still prevalent. That is what most Black artists do, and that’s great, but I want to work differently. I want to expand my audience’s experience of painting’s potential, painting’s possibilities.