Takako Yamaguchi

May 15–July 10, 2021

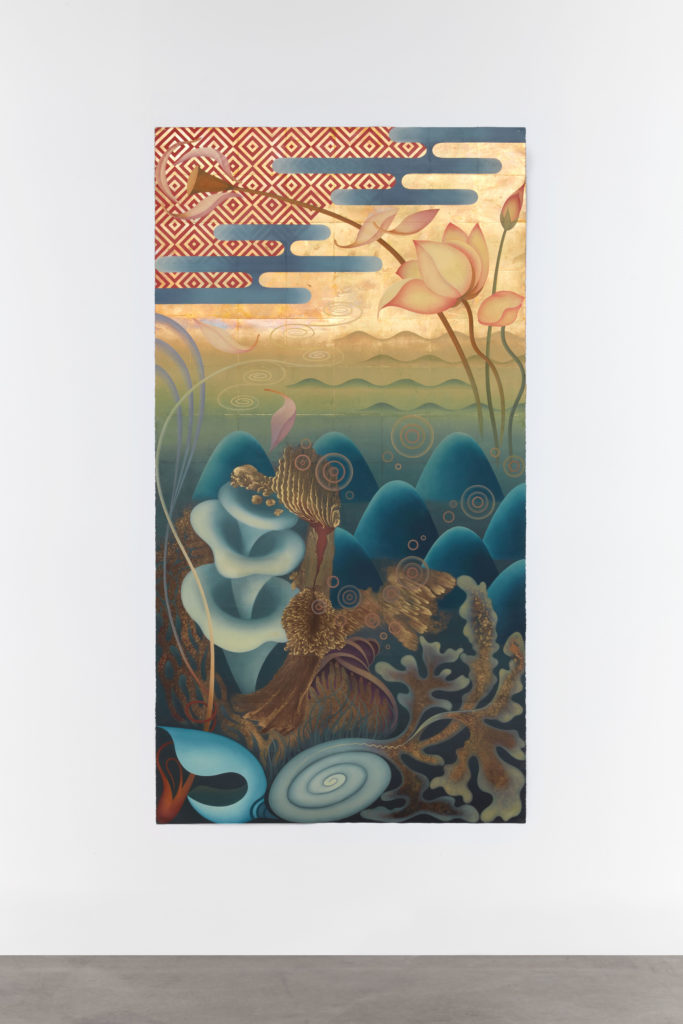

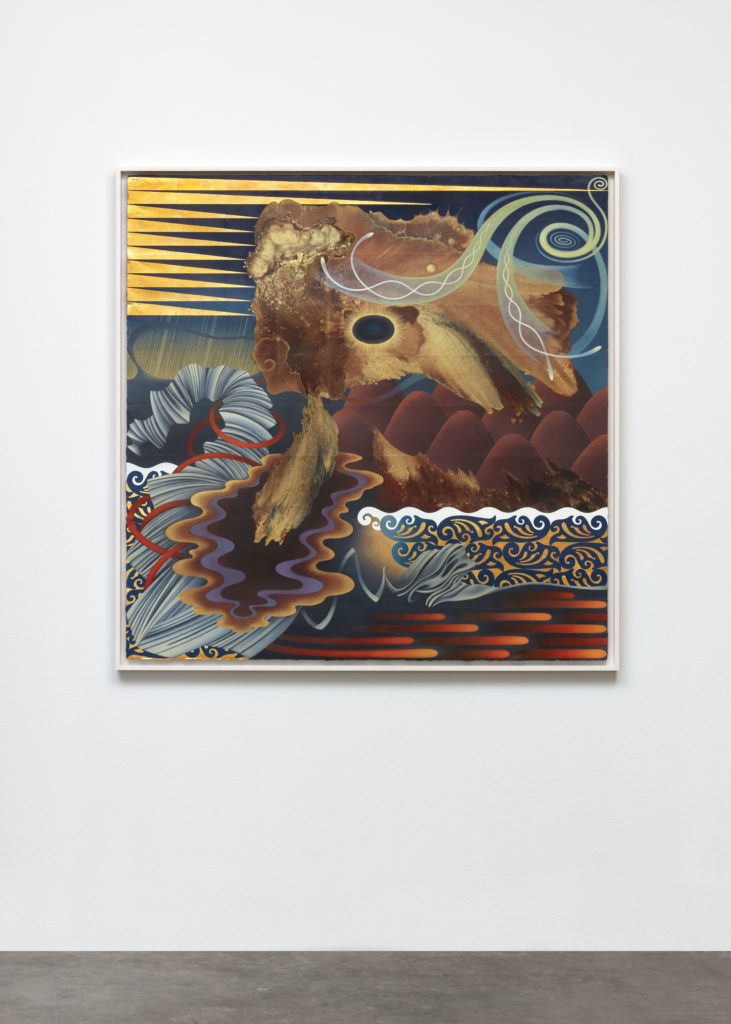

STARS is pleased to present its first solo exhibition by Los Angeles-based artist Takako Yamaguchi (b. 1952). Six oil paintings and works on paper depict a variety of landscapes and seascapes and span a wide spectrum of representational technologies: painting, drawing, illustration, graphic design, decorative arts. While stark moments of dissonance rise up from the frictions between these competing traditions, as a whole, each surface is home to a system of elements that collectively creates a portrait of transcendental balance. In Yamaguchi’s words, one way of describing her work is as “abstraction in reverse”—the singular order of each piece is the result of an unruly, accumulative process guided not by expressive freedom but instead emphatically composed captivity.

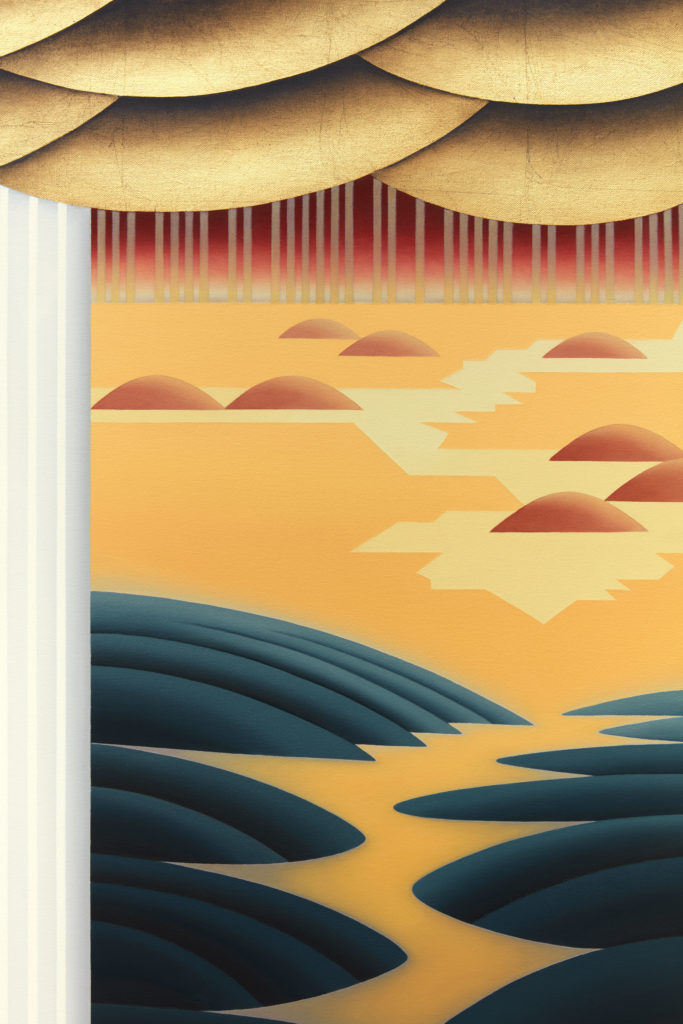

Each scene weaves together motifs distinctly drawn from natural realms that define themselves in opposition to one another: earth, air, sea. Many of these recur from piece to piece, revealing a repertoire of ideas that are so flat, their aggregate, incongruously, is brilliance. They are like the compacted pages of a book, whereas heavier vehicles might overburden and collapse the canvas. As again and always with the artist’s work, there are dichotomies and dialectics at play—sincerely at play, that is, engaged in games that eschew dour pretensions or grandiose formulas.

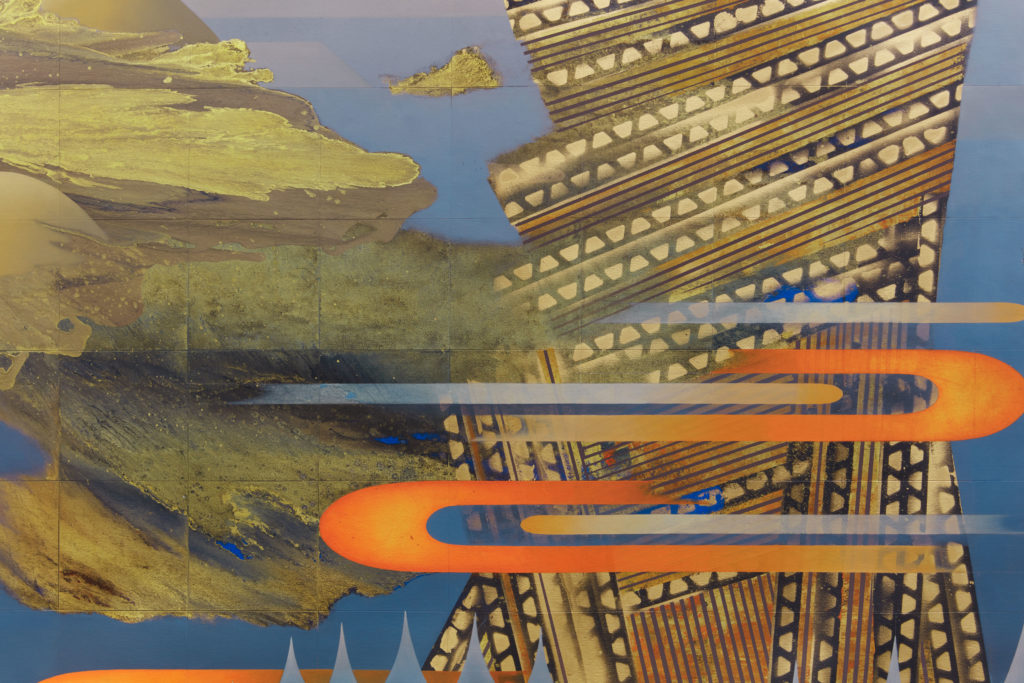

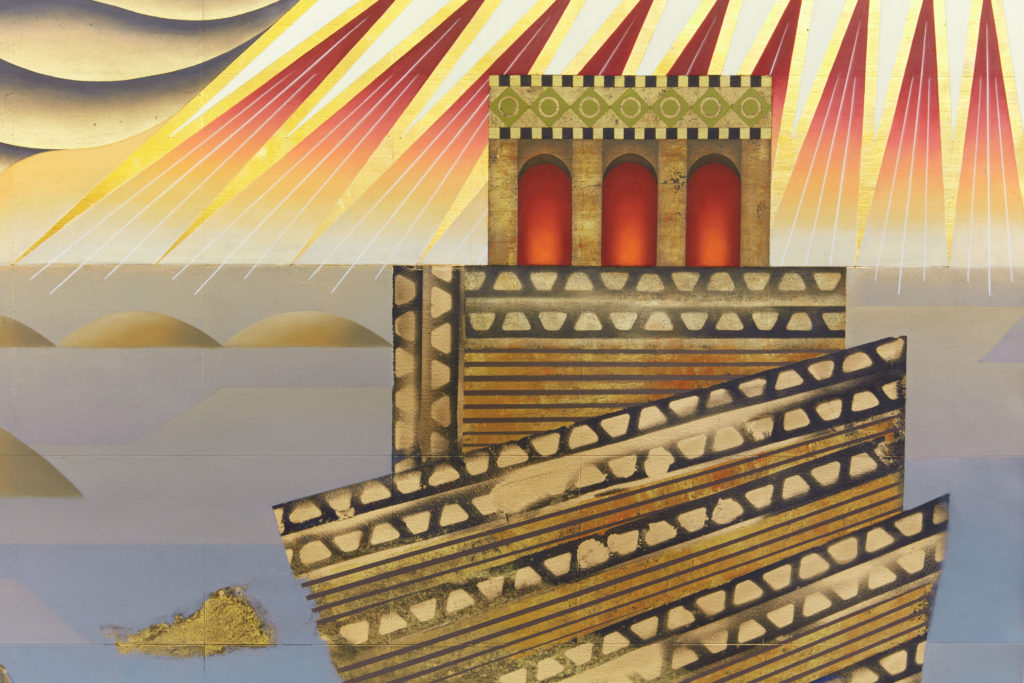

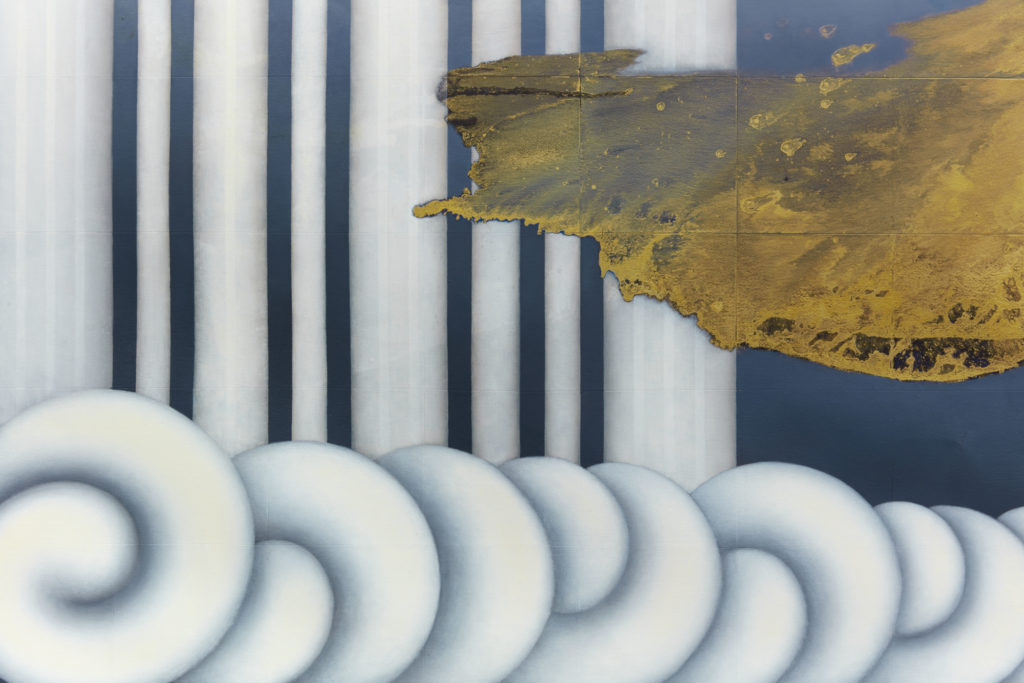

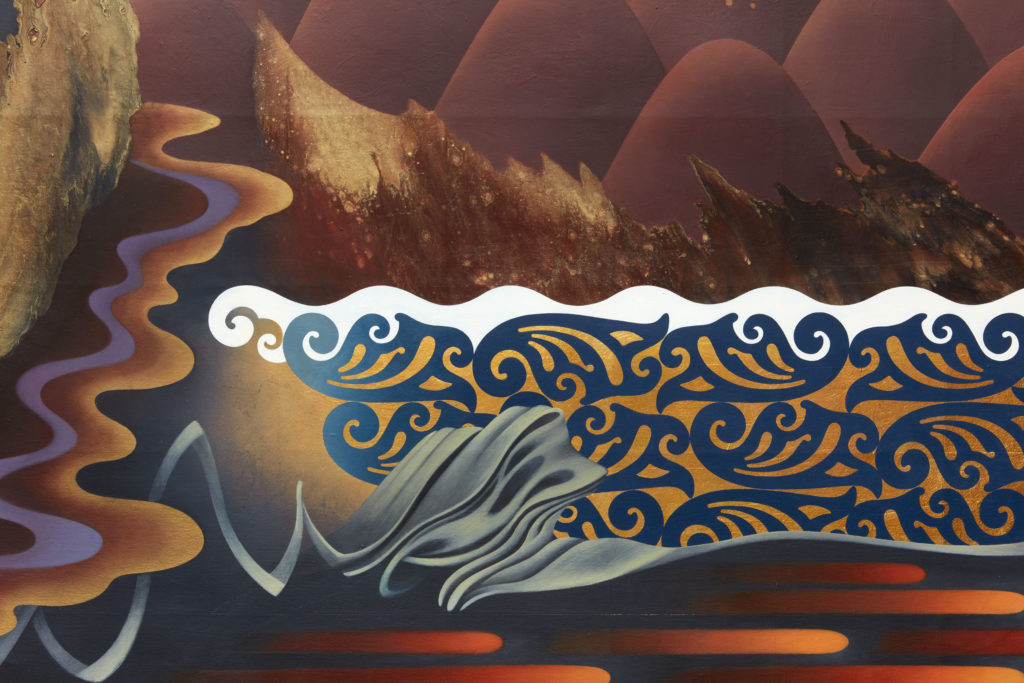

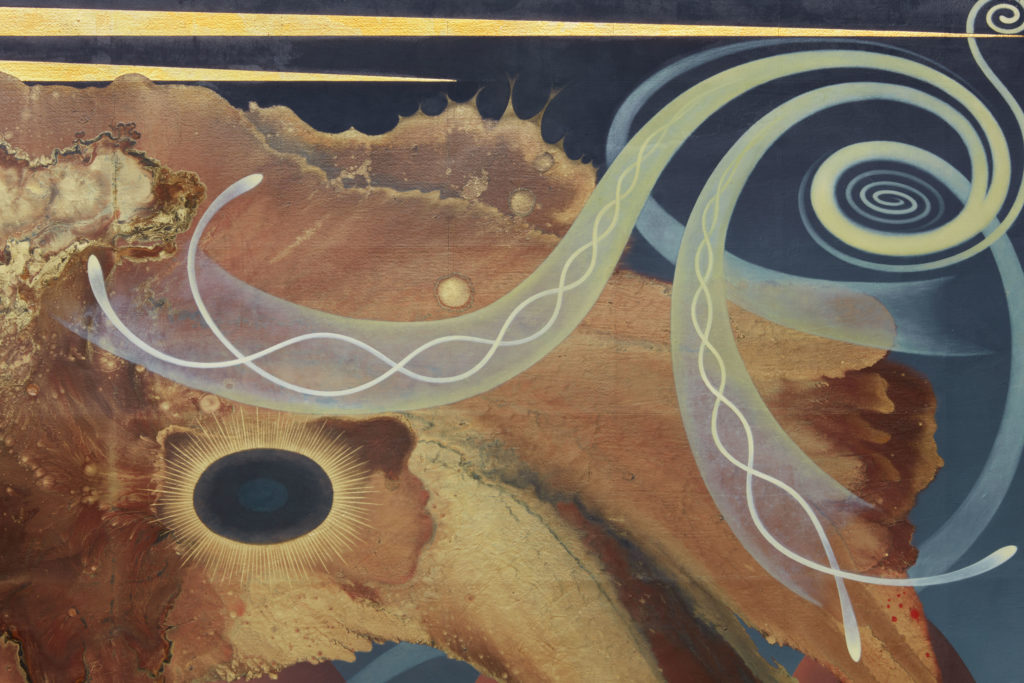

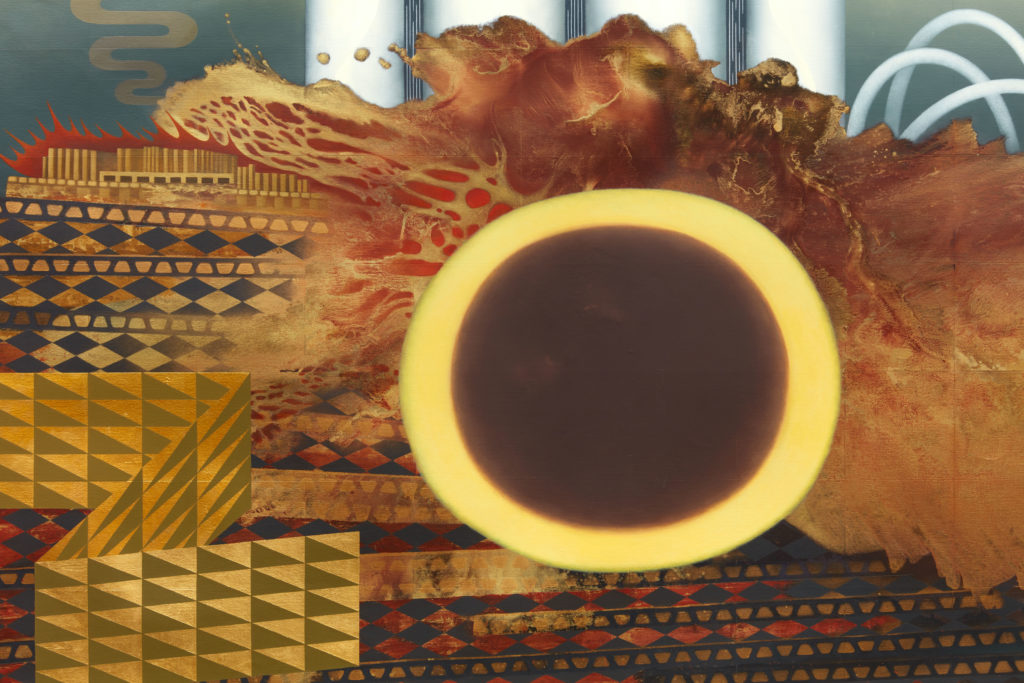

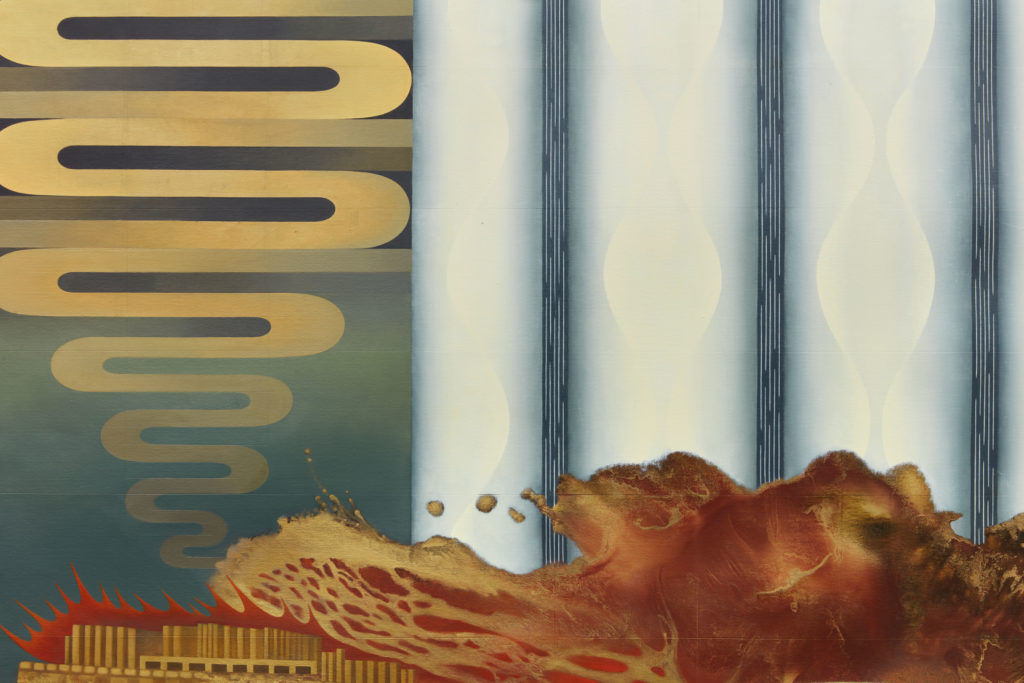

One such motif is the outlines of islands that protrude from water and the immaculate monotony of a sine wave… the hard-edged, continuous S-shaped spirals whose flatness induces an Op Art effect… the sinuous, meandering coils that drip lugubriously from lily pads, sprout up from sea beds and towards the sky like amphibian vines, or erupt from the cosmos in pairs, twirling together like DNA…

There are schools of cursory, handmade marks that give negative spaces the sense of a directional current and more controlled, jagged triangles that imbue others with the heat of searing light. Rigid columns are joined with undulating mounds above—an optically reversible figure doubles as rain cascading down from clouds or tree trunks extending upwards to their leafy crowns. Then there are chaotic passages spilled across some canvases, the messiness of which underscores how each image is a self-regulating ecosystem unto itself.

The works on view were made between 1998 and 2008, roughly the span of the Aughts, a decade whose historical classification still prompts confusion. “The nameless decade” has floated as one particularly ironic possible moniker for this epoch whose significance is largely rooted in the arbitrary consequence of the start of Western history’s third millennium. In a sense, Yamaguchi’s work has been met with similar confusion. Often throughout her career, exhibitions, primarily in Southern California—where she has worked for more than four decades since departing her native Japan in 1973—have framed her as an intriguing outlier, without developing much of a construct for contextualizing her practice as, conversely, a place of confluence.

Since the 1970s and 1980s, Yamaguchi has frequently been classified as an artist of the Pattern and Decoration movement, a mantle she has worn willingly, though not with the ideological conviction of some others. To these points, rather than in the service of a thesis or movement, the artist has observed that her work “is not about anything,” that her “research is more casual than deliberate;” her stance “self-feminizing ” and “self-orientalising;” and insofar as donning the costume of art historical codification, she has even characterized her attitude as like “dressing up in a kimono to please the college professor,” thus cheerfully, if also subversively, performing the roles that the white and male-dominated art world would inevitably assign to her, an Asian woman, regardless.

More recently when the work has been shown in contexts that anchor it to the tradition of Pattern and Decoration, or more broadly, in opposition to mainstream contemporary art—for instance, as non-fine art or as non-Western art— these feel exceptionally dated and limited. This is not only in light of changing consciousness around cultural hegemony and white supremacy, but also, more to the point of the particularities of Yamaguchi’s practice itself, how its substance rests in its uniquely divided and dispersed hybridity of influences and stylistic approaches. One would have to strain to picture this work as outside or beyond discourses relevant to painting today, when it is so clearly in the middle of them.